Introduction

A few weeks ago Beamr reached a historic milestone, which got everyone in the company excited. It was triggered by a rather formal announcement from the US Patent Office, in their typical “dry” language: “THE APPLICATION IDENTIFIED ABOVE HAS BEEN EXAMINED AND IS ALLOWED FOR ISSUANCE AS A PATENT”. We’ve received such announcements many times before, from the USPTO and from other national patent offices, but this one was special: It meant that the Beamr patent portfolio has now grown to 50 granted patents!

We have always believed that a strong IP portfolio is extremely important for an innovative technology company, and invested a lot of human and capital resources over the years to build it. So we thought that this anniversary would be a good opportunity to reflect back on our IP journey, and share some lessons we learned along the way, which might come in handy to others who are pursuing similar paths.

Starting With Image Optimization

Beamr was established in 2009, and the first technology we developed was for optimizing images – reducing their file size while retaining their subjective quality. In order to verify that subjective quality is preserved, we needed a way to accurately measure it, and since existing quality metrics at the time were not reliable enough (e.g. PSNR, SSIM), we developed our own quality metric, which was specifically tuned to detect the artifacts of block-based compression.

Our first patent applications covered the components of the quality measure itself, and its usage in a system for “recompressing” images or video frames. The system takes a source image or a video frame, compresses it at various compression levels, and then compares the compressed versions to the source. Finally, it selects the compressed version that is smallest in file size, but still retains the full quality of the source, as measured by our quality metric.

After these initial patent applications which covered the basic method we were using for optimization, we submitted a few more patent applications which covered additional aspects of the optimization process. For example, we found that sometimes when you increase the compression level, the quality of the image increases, and vice versa. This is counter-intuitive, since typically increasing the compression reduces image quality, but it does happen in certain situations. It means that the relationship between quality and compression is not “monotonic”, which makes finding the optimal compression level quite challenging. So we devised a method to solve this issue of non-monotony, and filed a separate patent application for it.

Another issue we wanted to address was the fact that some images could not be optimized – every compression level we tried would result in quality reduction, and eventually we just copied the source image to the output. In order to save CPU cycles, we wanted to refrain from even trying to optimize such images. Therefore, we developed an algorithm which determines whether the source image is “highly compressed” (meaning that it can’t be optimized without compromising quality), based on analyzing the source image itself. And of course – we submitted a patent application on this algorithm as well.

As we continued to develop the technology, we found that some images required special treatment due to specific content or characteristics of the images. So we filed additional patent applications on algorithms we developed for configuring our quality metric for specific types of images, such as synthetic (computer-generated) images and images with vivid colors (chroma-rich).

Extending to Video Optimization

Optimizing images turned out to be very valuable for improving the workflow of professional photographers, reducing page load time for web services, and improving the UX for mobile photo apps. But with video reaching 80% of total Internet bandwidth, it was clear that we needed to extend our technology to support optimizing full video streams. As our technology evolved, so did our patent portfolio: We filed patent applications on the full system of taking a source video, decoding it, encoding each frame with several candidate compression levels, selecting the optimal compression level for that frame, and moving on to the next frame. We also filed patent applications on extending the quality measure with additional components that were designed specifically for video: For example, a temporal component that measures the difference in the “temporal flow” of two successive frames using different compression levels. Special handling of real or simulated “film grain”, which is widely used in today’s movie and TV productions, was the subject of another patent application.

When integrating our quality measure and control mechanism (which sets the candidate compression levels) with various video encoders, we came to the conclusion that we needed a way to save and reload a “state” of the encoder without modifying the encoder internals, and of course – patented this method as well. Additional patents were filed on a method to optimize video streams on the basis of a GOP (Group of Pictures) rather than a frame, and on a system that improves performance by determining the optimal compression level based on sampled segments instead of optimizing the whole stream.

Embracing Video Encoding

In 2016 Beamr acquired Vanguard Video, the leading provider of software H.264 and HEVC encoders. We integrated our optimization technology into Vanguard Video’s encoders, creating a system that optimized video while encoding it. We call this CABR, and obviously we filed a patent on the integrated system. For more information about CABR, see our blog post “A Deep Dive into CABR”.

With the acquisition of Vanguard, we didn’t just get access to the world’s best SW encoders. We also gained a portfolio of video encoding patents developed by Vanguard Video, which we continued to extend in the years since the acquisition. These patents cover unique algorithms for intra prediction, motion estimation, complexity analysis, fading and scene change analysis, adaptive pre-processing, rate control, transform and block type decisions, film grain estimation and artifact elimination.

In addition to encoding and optimization, we’ve also filed patents on technologies developed for specific products. For example, some of our customers wanted to use our image optimization technology while creating lower-resolution preview images, so we patented a method for fast and high-quality resizing of an image. Another patent application was filed on an efficient method of generating a transport stream, which was used in our Beamr Optimizer and Beamr Transcoder products.

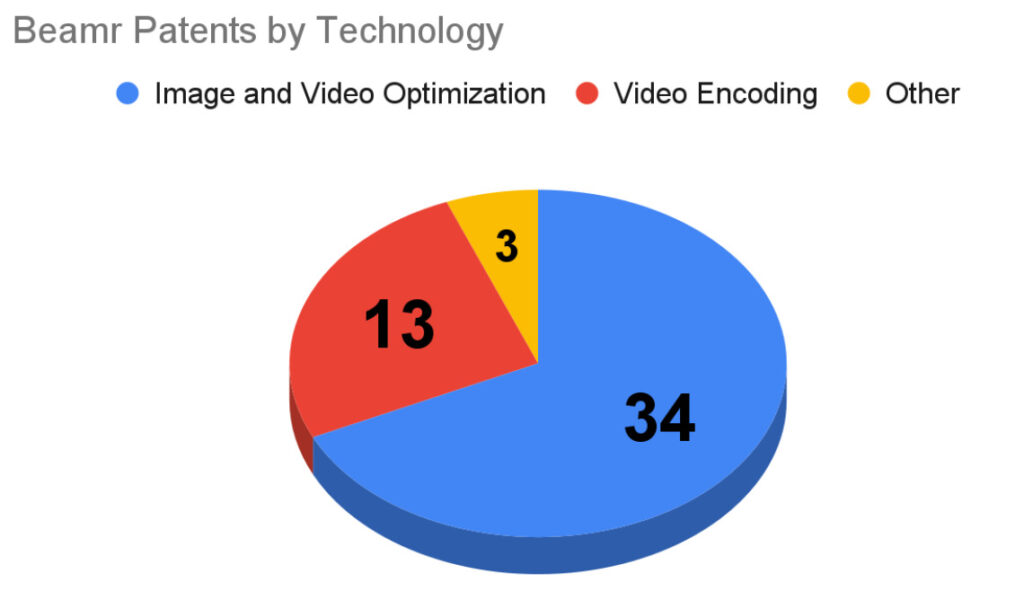

The chart below shows the split of our 50 patents by the type of technology.

Patent Strategy – Whether and Where to File

Our patent portfolio was built to protect our inventions and novel developments, while at the same time establish the validity of our technology. It’s common knowledge that filing for a patent is a time and money consuming endeavor. Therefore, prior to filing each patent application we ask ourselves: Is this a novel solution to an interesting problem? Is it important to us to protect it? Is it sufficiently tangible (and explainable) to be patentable? Only when the answer to all these questions is a resounding yes, we proceed to file a corresponding patent application.

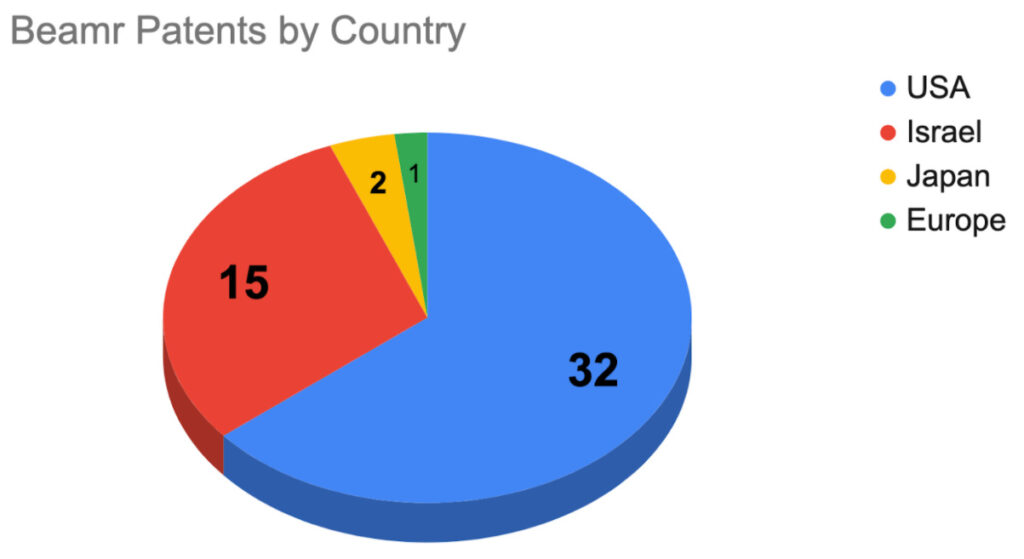

Geographically speaking, you need to consider where you plan to market your products, because that’s where you want your inventions protected. We have always been quite heavily focused on the US market, making that a natural jurisdiction for us. Thus, all our applications were submitted to the US Patent Office (USPTO). In addition, all applications that were invented in Beamr’s Israeli R&D center were also submitted to the Israeli Patent Office (ILPTO). Early on, we also submitted some of the applications in Europe and Japan, as we expanded our sales activities to these markets. However, our experience showed that the additional translation costs (not only of the patent application itself, but also of documents cited by an Office Action to which we needed to respond), as well as the need to pay EU patent fees in each selected country, made this choice less cost effective. Therefore, in recent years we have focused our filings mainly on the US and Israel.

The chart below shows the split of our 50 patents by the country in which they were issued.

Patent Process – How to File

The process which starts with an idea, or even an implemented system based on that idea, and ends in a granted patent – is definitely not a short or easy one.

Many patents start their lifecycle as Provisional Applications. This type of application has several benefits: It doesn’t require writing formal patent claims or an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS), it has a lower filing fee than a regular application, and it establishes a priority date for subsequent patent filings. The next step can be a PCT, which acts as a joint base for submission in various jurisdictions. Then the search report and IDS are performed, followed by filing national applications in the selected jurisdictions. Most of our initial patent applications went through the full process described above, but in some cases, particularly when time was of the essence, we skipped the provisional or PCT steps, and directly filed national applications.

For a national application, the invention needs to be distilled into a set of claims, making sure that they are broad enough to be effective, while constrained enough to be allowable, and that they follow the regulations of the specific jurisdiction regarding dependencies, language etc. This is a delicate process, and at this stage it is important to have a highly experienced patent attorney that knows the ins and outs of filing in different countries. For the past 12 years, since filing our first provisional patent, we were very fortunate to work with several excellent patent attorneys at the Reinhold Cohen Group, one of the leading IP firms in Israel, and we would like to take this opportunity to thank them for accompanying us through our IP journey.

After finalizing the patent claims, text and drawings, and filing the national application, what you need most is – patience… According to the USPTO, the average time between filing a non-provisional patent application and receiving the first response from the USPTO is around 15-16 months, and the total time until final disposition (grant or abandonment) is around 27 months. Add this time to the provisional and PCT process, and you are looking at several years between filing the initial provisional application and receiving the final grant notice. In some cases it’s possible to speed up the process by using the option of a modified examination in one jurisdiction, after the application gained allowance in another jurisdiction.

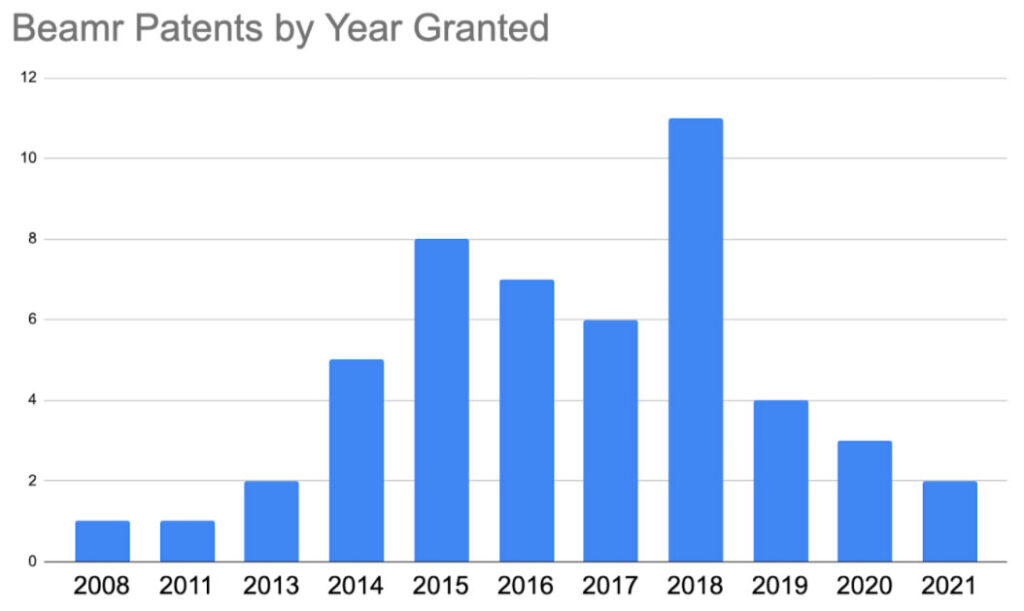

The chart below shows the number of granted patents Beamr has received in each passing year.

Sometimes, the invention, description and claims are straightforward enough that the examiner is convinced and simply allows the application as filed. However, this is quite a rare occurrence. Usually there is a process of Office Actions – where the examiner sends a written opinion, quoting prior art s/he believes is relevant to the invention and possibly rejecting some or even all the claims based on this prior art. We review the Office Action and decide on the next step: In some cases a simple clarification is required in order to make the novelty of our invention stand out. In others we find that adding some limitation to the claims makes it distinctive over the prior art. We then submit a response to the examiner, which may result either in acceptance or in another Office Action. Occasionally we choose to perform an interview with the examiner to better understand the objections, and discuss modifications that can bring the claims into allowance.

Finally, after what is sometimes a smooth, and sometimes a slightly bumpy route, hopefully a Notice Of Allowance is received. This means that once filing fees are paid – we have another granted patent! In some cases, at this point we decide to proceed with a divisional application, a continuation or continuation in part – which means that we claim additional aspects of the described invention in a follow up application, and then the patent cycle starts once again…

Summary

Receiving our 50th patent was a great opportunity to reflect back on the company’s IP journey over the past 12 years. It was a long and winding road, which will hopefully continue far into the future, with more patent applications, office actions and new grants to come.

Speaking of new grants – as this blog post went to press, we were informed that our 51st patent was granted! This patent covers “Auto-VISTA”, a method of “crowdsourcing” subjective user opinions on video quality, and aggregating the results to obtain meaningful metrics. You can learn more about Auto-VISTA in Episode 34 of The Video Insiders podcast.